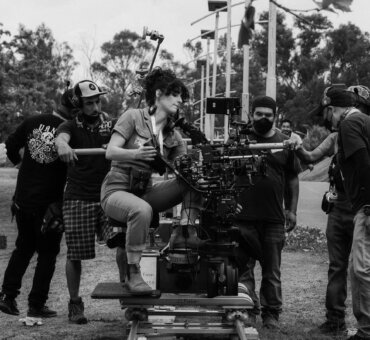

Danny Madden (a.k.a. Ornana) has one rule: Make films the hard way, or don’t make them at all. “Sometimes it’s easy to look for tricks, or to want to master your craft to the point where you know what you’re doing and it gets easier. But if you get to that point, where what you’re doing is easy, then you’ve really lost something.”

True to his word, Danny’s projects have all been very, very difficult to make. Whether it was creating thousands of schoolbook doodles for his breakout short film (Notes on) Biology; hand illustrating (on recycled paper, no less) the 10-minute award-winning animation Confusion Through Sand; or directing young, first-time actors for his live-action project Euphonia, Danny’s films all contain an inherent struggle that makes them worthwhile for not only him ⎯ but also for us, his audience.

Here’s our conversation with Danny Madden about why doing things the easy way is almost never worth your time.

How did you get into animation?

When I moved to Colorado, I thought I’d live a mountain life, read books, chill out. But after a few months, that filmmaking itch really struck. I needed to make something. But I looked around and there weren’t a whole lot of people interested in that kind of thing. So I was like, All right, how do I make a movie by myself? That’s when I started doodling. I kind of tumbled into the animation world.

The great thing is that you’re only inhibited by what you can’t draw. You can do anything you want with the camera. You can do anything you want with the characters. It was this great way of practicing filmmaking that wasn’t expensive at all. And if you spent a little time on sound design and editing, you could end up with something watchable.

What did this actually look like? Were you staying up at night drawing a bunch of panels?

Between my shift teaching snowboarding on the mountain during the day and working in a restaurant at night, I’d pop into the library where they had this huge wall of CDs. Any album you could think of. This was the library in Aspen, so you can imagine they were well funded. They had these listening booths you could go into, and sit and listen to whatever record you wanted, for as long as you wanted. It was the perfect place to decompress and transition from one job to the other. So I sat in there with a notebook, listened to music, and animated a goofy elephant thing.

Is that how (Notes on) Biology was born?

(Notes on) Biology was based on an actual flip book I’d done using my school notes. I was like, “Great. There’s my raw source material.” Then I built a frame of a story around that. I’ve always been a story person. Just having a cool 30-second Internet video of flashy stuff doesn’t do it for me. So with (Notes on) Biology, it became about how this kid’s life reflects what’s going on with this elephant. It’s about how we express things. It’s trying to say something about art and how people adapt to what’s happening around them. That was always my solution for something that didn’t hold my interest in school. I was like, “Well, I’ll just do something that is interesting to me.” And since I was sitting in class and had a bunch of paper, it was doodling.

I’m not interested in seeing things that were easy for someone else to make… difficulty is something I value in any work.

Do you have a certain process for your projects?

No. They’re all very different. But I always need to feel like How the hell am I going to do this? I need that tension of wondering whether something is going to work. Sometimes I get jealous of my writer friends, though, because they’ll write something great and then it’s done. But when I do that part, it’s step 1 of 390.

Why filmmaking, then, when it’s so difficult?

Well, the difficulty is exactly the thing. There’s this Jim Henson quote that says, “If it was easy, everyone would be doing it.” That’s become a mantra for me. I’m not interested in seeing things that were easy for someone else to make. So how hypocritical would it be of me to make things in an easy way? So yeah, difficulty is something I value in any work.

The struggle is important.

Absolutely. I think it comes through. Even if people don’t realize there was a struggle involved, it grabs them. In some subconscious way, the effort comes through. Sometimes it’s easy to look for tricks, or to want to master your craft to the point where you know what you’re doing and it gets easier. But if you get to that point, where what you’re doing is easy, then you’ve really lost something. What you’re doing starts to blend in. There is something about taking shortcuts that makes your work look exactly like the work of everyone else who’s taking shortcuts. So I make sure I do stupid things to keep the work difficult.

You’ll always hear people talking about how hard films are to make and how much time they take. Those are the exact reasons to make them.

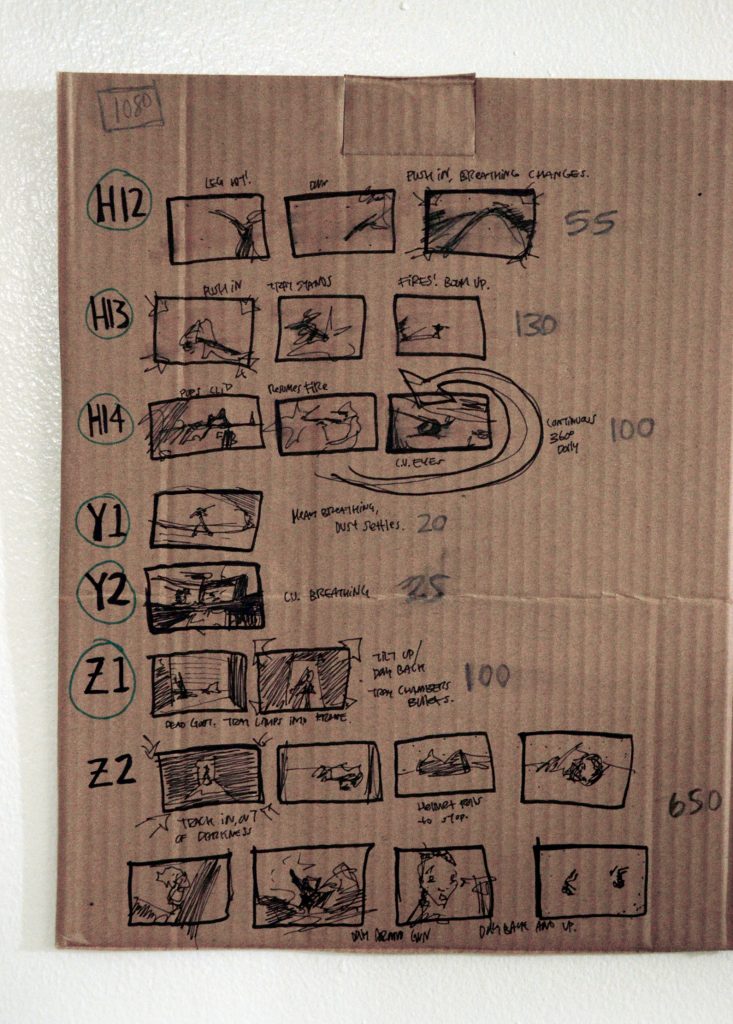

For example, I drew Confusion Through Sand with markers on recycled paper. And we drew the backgrounds on every frame. It’s stupid to draw the backgrounds on every frame. It’s crazy. But at the same time, it came from a place of, “This is the second animation I’ve ever done, and I don’t know anything else. This will work.” And when you come out of it, you realize that the difficulty is what made it worth it.

If there’s one thing I’d communicate to filmmakers, it’s that you’ll always hear people talking about how hard films are to make and how much time they take. Those are the exact reasons to make them. And of course it helps when you find people to work with who share your philosophy. I’ve been lucky to find people like [producers] Jim Cummings and Benjamin Weissner. And of course my brother Will Madden, who I’ve forced into my films since he was three. Together we’ve been able to really grow this whole Ornana thing.

One thing I love about your style is how imperfect it is. How do you go about improving on a style that’s inherently imperfect?

A lot of it has been about using my limitations. Like with Confusion Through Sand, I didn’t have the confidence to stay on model with the character design. So I decided, okay, he’s going to look different throughout the film. And when you pause some shots, it doesn’t even look like the same character. But that ends up being okay.

When I made (Notes on) Biology, the reason it looks the way it does is because that was literally the best I could draw at the time. You start gaining confidence in that. And for me, it starts feeling alive in that way. I’ve heard this phrase: Showing the hand of man. The rawness brings me in as a viewer in a way that very clean, pristine visuals don’t always do.

Confusion Through Sand somehow feels very emotional and human even though it’s very rough. Was that a conscious effect you were going for?

I think for me, just as a process thing, I have a bouncy personality. In order to do something like animation, I need to imbue velocity into the process. I’m actually going fast. I’m scribbling. My hand is blurring around the page. I’m listening to fast music. That process is reflected in the imagery. In the end, there’s graphite all over my hands, and I have to go wash them. I love that. It’s so exciting to me.

When you get your hands dirty and make a project despite (and maybe because of) the difficulties, that’s when your true creativity comes into play. Sure, it may not be the comfortable choice, but maybe that’s the whole point.