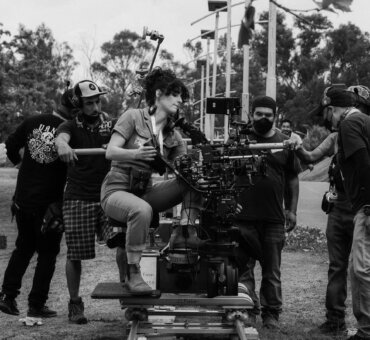

It would make sense for most first-time narrative directors to keep the bar low. Shoot locally. Limit variables. Make something simple. Don’t, for example, incorporate a sacred bull-jumping ceremony in a remote Ethiopian village. Don’t, for example, shoot the entire film in a language you don’t understand. But of course Joey L. isn’t most first-time directors. And People of the Delta is not most films. Set in a brutal section of Ethiopia known as the Omo Valley, People of the Delta is the first narrative film of its kind ⎯ so unique that it will live in an Ethiopian culture museum as an ethnographic study of the region.

“If you have an idea for something that no one has ever seen before, it’s probably worthwhile to pursue it,” Joey told us. But then again he also told us this: “It was actually the hardest project I’ve ever worked on. Even harder than going to the front lines against ISIS…”

If there’s a lesson here, this might be it: If you want to make something nobody has ever seen before, it’s going to be very, very difficult.

Here’s Joey L.

Musicbed: How’d this project happen?

I think the origin was my relationship with Uri, who is one of the main cast members in the film. When I first started doing photo projects in the Omo Valley region, Uri would be my interpreter/the guy who helped me carry my bags/my camping helper. We became fast friends. And I started joking with him that when it came time for him to do his bull-jumping ceremony — which is a rite of passage similar to a bar mitzvah or Sweet Sixteen party — I would come for it. I would be his guest. Then I started thinking it would be an amazing feat to do a narrative film in the Omo Valley that incorporated Uri’s bull-jumping ceremony into the mix.

The bull-jumping ceremony was a kind of jumping-off point for the project?

Yes. The film is obviously a narrative film, but it’s very much based on real events. A lot of the scenes are real because it’s just impossible to fake them, or better to just shoot the real thing. The Hamar tribe is never going to fake a bull jump for a film crew. It’s taboo for their culture to put on fake bull jumps, and as a filmmaker you must respect this. So that part is completely real. That’s Uri’s actual bull-jumping ceremony. We scripted a broader conversation around it to better tell a story, but the ceremony is the real thing.

Why make a fictional film about this area as opposed to a documentary?

I just wanted to give it a shot. There have been a lot of great documentaries about the Omo Valley and its tribes. That ship has sailed about a million times. I guess I wanted a challenge. To make the first narrative film in that region. I also believed these people could carry a story and make something fresh that nobody had ever seen before. And by doing that, we could draw new eyeballs to the issues, get a new kind of audience who has no interest in watching another tribe documentary.

I’m not a journalist. I’m a storyteller. And these people are storytellers too. Story is how they communicate among themselves.

You can only watch so many of those.

Right. A lot of them are very good but there’s a wall. Journalists can only get so close to their subjects. They can only get so involved. Which is a good thing because that’s journalism. But I’m not a journalist. I’m a storyteller. And these people are storytellers too. Story is how they communicate among themselves. So I thought if we could just give them a medium, like a film camera, that would be a unique way to tell a story that has not been done before.

This was your first narrative film?

Yeah. The first film I ever directed that was not a documentary. And I made all the mistakes a first-time director makes. We had a super-low budget. We shot in a place without electricity. It was in a foreign language. The cast had never seen a movie before. So it was in no way, shape, or form easy. It was actually the hardest project I’ve ever worked on. Even harder than going to the front lines against ISIS and seeing a war. But in the end we made something very unique, and it’s a good proof of concept for other projects I want to make in the future.

Why do something so hard for your first film?

I want to tell fresh new stories. If you have an idea for something that no one has ever seen before, it’s probably worthwhile to pursue it. I had the idea for this film in my head. There was no way I was not going to let it happen. And in a lot of ways, this project ended up being my film school. Even if everything had gone to shit and we’d gotten nothing, it would have been worth it because of how much I learned and the talented people who became part of the crew, like Sean Stiegemeier, the cinematographer. It’s like how people say that instead of going to film school you should just make your first film. This film forced me to learn.

If you have an idea for something that no one has ever seen before, it’s probably worthwhile to pursue it.

You mentioned that some of these people had never seen a film before. Did they understand the project?

Big time. The first thing you have to do in those cultures is explain your intentions to the elders — especially if you’re going to bring a crew of seven people. They’re not going to put up with anything they don’t know about, nor should you as a guest expect them to. That’s why, for example, we don’t show much violence. That’s out of respect for the elders and their request. And I truly believe the archnemesis of the film is the drought, so the fighting between tribes itself was not important in the film. So they knew everything about the film and understood exactly what we were doing. I even had storyboards made up of the whole thing. I hired a talented artist in Canada to storyboard every single frame. Then I walked them through it. It was grueling, but in the end they knew exactly what was going on, and became a collaborative process which everyone was excited to be a part of.

What was the local response to the film?

They understand that it’s important. The thing is, the armed conflicts between the Dassanach and Hamar tribes are in direct relationship to the environment and weather. That’s something that people — even people living in the cities of Ethiopia — don’t understand. They’d wrongly say these tribal people are backward savages, killing one another. But the fact of the matter is, the land is the enemy. When it’s a dry season, there’s going to be fighting because there are limited resources. That’s what we were able to show with this film. And I think they see it as a really honest depiction.

This was a passion project. As a filmmaker, these are the types of things I want to do in the future. Strange things that move people.

What’s it like directing performances when you’re not even sure what people are saying?

It was very challenging, but this is how it worked — We would know the basic scenario, character, and the main points we were trying to hit. But rather than fully scripting lines and trying to memorize them line by line, I’d just let them talk long form. We did these really long takes, and most of the time they ended up saying things that were way better than what I had written. It was a slow process, but it was the best way to do it to keep things natural. And even though I didn’t understand what they were saying as the words flowed live, I could still monitor other things, like tone and expression. But really, it came down to having good translators. Uri was right beside me the whole time, and I would ask, “What did they talk about? Did they hit this?” But I’m not going to pretend I could understand. So there was a lot of trust that had to happen there.

What happens with the film now?

Well, let’s be honest. This film has no place on television. Frankly, it’s too weird. And it’s too short to be in theaters. It really has no place in the world except for a museum and on Vimeo. And even then, I’m surprised how many people have watched it. It’s a super-niche audience, but I think that’s a good thing for a film like this. It wasn’t made for the masses. This was a passion project. As a filmmaker, these are the types of things I want to do in the future. Strange things that move people. If I hadn’t made this film, nobody else would have. If I’d tried to pitch it to normal investors and explained that it’s about two remote groups in Ethiopia you’ve never heard about, none of those people would ever invest in that. Instead, it was self-funded via teaching photography workshops and crowdsourcing supporters from the photography and film community online. Nobody from the conventional film world would care unless we actually went out and made it. So that’s what we did.