Film editors bat cleanup in the long, long, super long process that ends if all goes well with a finished film. They take raw material and turn it into something clean, cohesive, and engaging. They’re not so different from a chef in that way. And they require just as diverse a skill set. “Being an editor is equal parts creative, craft, and pure nerd,” Lucas Harger an editor at the creative studio Bruton Stroube told us recently. “And I am exceptionally nerdy.”

To continue mixing our metaphors: Editors are surgeons, storytellers, and mad scientists who somehow manage to bring disparate hunks of material to life. They wield a scalpel in one hand, and a butcher’s cleaver in the other.

We talked to Lucas recently about editing.

Musicbed: What’s the best thing about being an editor?

For me, it’s when you see an audience grasp something that you crafted very intentionally but would be very easy for them to miss. That’s honestly why I edit. Films are this huge process, and I’m given the responsibility to deliver the final product. So when the audience grasps a subtlety or a subtext, it means the entire process was handled properly. Basically it’s the shit.

And I should be clear that the intricacies I’m talking about aren’t related to techniques or tools. It’s all about emotions and response. It’s about the high-level ideas a director and I talk about and craft. Those are the things I get excited about an audience picking up on. Not necessarily someone recognizing, like, “Oh, man! Dope match cut!”

I remember reading about a scene in Jaws where a dead body appears and makes the audience jump. It took them weeks to get the timing right for the audience to have that response.

Frames matter, man. One frame, two frames, three frames. People roll their eyes when you talk like that, but a few frames really can make the difference. Nudge it one way or the other, and you get a completely different emotional response to a scene. It’s incredible.

Have you developed a playbook for getting certain responses?

It’s always different. Each scene calls for its own way to be cut. There might be certain tropes or tricks you can employ. Certain music decisions, sound design, or pacing. But each scene calls for its own specific vibe in order to work. I have a few tricks, but I don’t have a playbook.

How have you helped yourself improve as an editor?

For me, it came down to editing a ton, and editing in a lot of different genres. I also did a lot of reading. I still do a lot of reading. I scoured the Internet for master’s level film programs at different colleges, and then I stole their required reading lists. I should be set for three years of reading. I try to get through one book on the syllabi a month.

I also keep an extensive journal of different thoughts I have about the craft. Different things I’ve learned. New theories I’d like to try out. If I see something that sparks my interest, I write a paragraph about it, and then I try to employ it on a project. So it’s been a lot of editing, a lot of reading, and a lot of watching. Those are the things I do on a daily basis to improve as an editor.

You aren’t just an editor. You also need to understand directing, you need to understand cinematography…

Which books have helped the most so far?

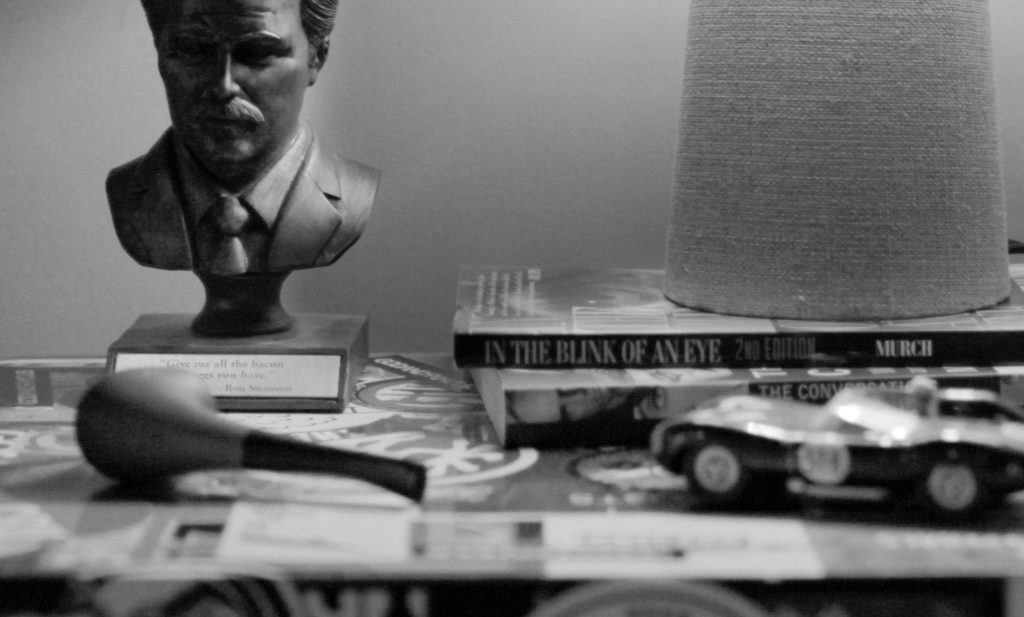

Everybody says it, but Walter Murch. Anything Walter Murch has written. In the Blink of an Eye. The Conversations. Those are two must-reads in pretty much everybody’s opinion. I just finished reading Kazan on Directing by Elia Kazan. He has so many amazing things to say, and that book is basically a compilation of all his notes and journals about the specific plays and films he made. It’s an amazing book.

So you read books that aren’t just about editing.

You have to take a holistic approach to the process. You aren’t just an editor. You also need to understand directing, you need to understand cinematography — not from the standpoint of being able to perform those crafts, but understanding what these craftsmen are trying to accomplish in a particular moment. You need to know what they’re doing with a scene if you’re going to do that scene justice during the edit.

On the other side, you also need to understand the power of sound, the power of color. Those things are going to add so much, and you need to be aware of how they affect the final piece. I cut from a very sonic place. I rely on sound design. Until I tidy up my sequence, they will generally have 18 to 25 channels of audio. Understanding sound design and collaborating with the sound designer is huge for me.

I try to read books from every single department. Even costume design and set design. That stuff matters. You need to know why a particular take is better than another because of how the practical light was in the perfect position to illicit a certain vibe from the set. Maybe only a couple people pick up on it, but it’s there. That’s what makes an edit deep, having a trained eye to see those things and understand them.

Do you remember the last craft note you took?

I have a long-running note on the relationship between an editor and director. It has swung from the relationship being purely technical to being completely collaborative, and now it’s landed somewhere in the middle. I think the editor should be this technical extension of the director’s brain, but also understand the vision for the end product so he can offer ideas. One of the specific things I’ve been trying to employ lately is keeping conversations with the director at as high a level as possible. The specific tools I use to bring the vision to life, that’s my job. That’s what I’m proficient at. So let’s talk about how the audience should feel. Let’s talk about what we’re trying to communicate. Let’s talk about how we’re going to move from one act to the next.

You edit many different kinds of pieces. Do the techniques mostly translate?

Mostly, but some have their own unique challenges. Cutting for 30 seconds is so different than cutting for 30 minutes. And honestly, learning how to cut a really effective 30-second piece will pay dividends when you go to long form. Learning to communicate a lot of information in a short amount of time is a big artistic and creative challenge. If you can master that, then working on a longer piece will feel like the sandbags have been taken off your ankles.

What’s your approach in the long form? How do you hold someone’s attention for an hour?

Well, that’s the challenge, isn’t it? I tend to outline things with notecards. I watch all the footage and mentally process what I’ve seen; and then I craft the story horizontally on the wall with notecards. That way I can step back and get a sense of the emotional flow and rhythm of the piece. There might be a 30-minute section without any real emotional hit. What can I do there to build up an emotional peak that will break up this valley? Peaks and valleys both serve a purpose. You need one to have the other. If you’re going to be throwing a lot of information at the viewer, then you might need to break that up with an emotional peak. And vice versa. If the film is emotional for 40 minutes straight, that’s exhausting for the audience and soon nothing really matters. You’ve set the emotional bar too high.

Do you save the highest emotional peak for the end?

I don’t have a rule of thumb for saving the crescendo for any particular point. For me, the end should be the culmination of everything we’ve seen. Whether it’s wrapping up everything or purposefully unwrapping everything. There should be some sort of conclusion, but you don’t have to hit the audience over the head with it. It doesn’t need to be some massive climax. And sometimes it can be something totally off the wall.

At the end of Werner Herzog’s film Cave of Forgotten Dreams, they’re inside this cave looking at the oldest-known drawings made by man. And he has this perfect kind of wrap-up moment where you think the film could end. But then he starts talking about these radioactive crocodiles that live in the cave. It’s all completely made up, but he uses it to communicate a very specific point. It’s like this little addendum. You’ve watched this entire documentary and then it ends with radioactive crocodiles. It’s hilarious and perfect, but it’s not an emotional peak. It’s not some soaring statement about humanity. It catches you off guard. Then the film ends and you start drawing your own conclusions.

What is your approach with a documentary, where the narrative is a progression of ideas?

Well, I should say one very important thing is to always cut with the audience in mind. I think of myself as the first true audience. When I watch the raw footage, I make notes about how certain sections make me feel. Then I figure out how to enhance that feeling. How to craft it into something that will hit with the second audience.

It’s about building space for the viewers to put themselves into the film, to almost

Do you start from the beginning and work to the end?

I don’t have a specific process, except I never start from the beginning and work to the end. I also rarely start with the end. Normally I find a section I think would be fun to mess with, and I start

Throughout the whole editing process, I’m constantly asking myself, What is the point of this part? Is this section doing its job? If it doesn’t work with the overall purpose of the film, I cut it. That’s why it’s so important to keep the audience in mind at all times. A lot of film editors say they’re keeping the audience in mind, but they’re not. You have to keep them in mind. You have to understand how each piece is going to make them feel, how each piece is going to land. You have to somehow figure out a way to package this footage and deliver it in the most meaningful way possible. That’s how you push a story forward.