Let’s talk about one of the most visually striking films to be released in recent memory — The Green Knight. Everything about this film just works, from the cinematography to the blend of practical and visual effects to the haunting score — it’s an incredible example of what happens when creative minds align in every department throughout every step of production.

Directed by David Lowery (A Ghost Story, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints) and shot by Andrew Droz Palermo (who also shot A Ghost Story) the film is an interpretation of a 14th-century chivalric poem titled Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Based on Welsh, Irish, and English stories (and French chivalric poetry), this medieval blockbuster follows King Arthur’s nephew, Gawain. The Green Knight unfurls at Christmastime, moving forward one year as Gawain sets off on his journey to fulfill his obligation to his shadowy nemesis at the Green Chapel. “The poem is a classic Christmas tale, and I love how the season and holiday are so thoroughly ingrained in the original text,” remarks Lowery. “I’m also a big fan of Christmas movies, and hoped that this might function as a slightly left-of-center Christmas film. The holiday is discussed quite a bit in the movie, even though there aren’t any Christmas trees, ornaments, and carols.”

For this bold reimagining of the medieval classic, Lowery and his team wanted a stark wintry palette heavy with grays and greens, in keeping with the rich color symbolism of its source text. Lowery also loves shooting in cold weather and sought to capture the feel of a 14th-century landscape in bleak, wintry shades (the color of Cahir Castle) and green tones:

“If I have any big regret, it’s that we didn’t start shooting sooner, because springtime started creeping up on us — you can see buds and blades of grass popping up in several scenes.”

Before heading into production, one of the notes Lowery initially gave Droz Palermo was to make the image feel 3D. While the film is not a “3D movie,” it’s worth breaking that note down as we attempt to understand how choosing your lenses and the type of sensor you shoot with can create images that conjure a particular reaction. So let’s look at how they shot The Green Knight and go over a few takeaways.

Going Wide

Lowery and Droz Palermo decided to go with the ALEXA 65 large format camera system — with the intention of capturing a grand sense of scale while telling an intimate and personal story. While the source material is just lines on an ancient page, the story of Gawain was one of the most popular Arthurian tales of its time. It circulated as an oral tradition for hundreds of years before anyone even wrote it down, and history has no idea who its author was. With plenty of motifs and symbols that would be familiar to a medieval audience (even if they are a little opaque to us now), the story has all the elements of a truly epic tale.

To really translate this sense of grandeur to the screen, the film is in 1.85:1 aspect ratio, shot mostly with a single camera setup. While keeping the overall visual tone of the film grounded, the shots often dip into surreal territory that is reminiscent of Apocalypse Now, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, or even Tarkovsky’s Solaris. Mysterious, glowing yellows, somber blues, and chilling reds completely overtake Gawain’s environments. If you need another modern example of inventive colorful cinematography, check out Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth, and buckle up.

Lowery has specifically referenced Bram Stoker’s Dracula as a heavy influence on the set pieces and overall look and feel of the film. This comes as no surprise, given Dracula’s particularly dark, contrast-heavy look with deep blacks and skin tones that pop from the shadows.

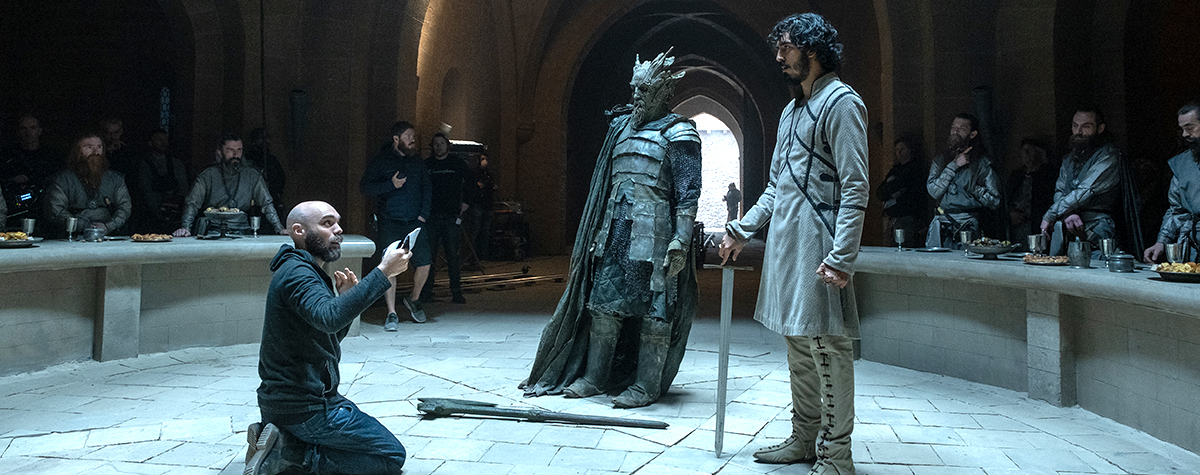

In terms of composition and blocking, the large format sensor of the camera enabled Droz Palermo to get as physically close to the subjects as possible while keeping the background and secondary characters all in frame without anything feeling warped or cramped. For example, there were action scenes where Droz Palermo would be so close to Gawain he’d almost touch him with the matte box.

They could pull off this tightness without the usual wide-angle distortion that comes with shooting on super-wide-angle lenses with a Super 35mm sensor thanks to ARRI’s camera technology. While using a 10mm or 12mm lens, Droz Palermo opted for the ARRI DNA Lens set due to the size and overall characteristics when shooting wide open. It’s choices like these that gave The Green Knight such a distinct look, setting it apart from many other modern fantasy films. The “big image” they were getting from the camera system really sold the scale of the film, but it didn’t make it the star of the show.

Staying Symmetrical

Although not every shot in The Green Knight is center-framed, or symmetrically composed, many of the establishing shots of Gawain have him perfectly in the center of the frame. While the meaning behind this decision is subjective and up to us as the audience to decide, the intention is very clear from Lowery and Droz Palermo. Gawain is the center of his universe, passing by different landscapes and characters throughout the narrative. A major theme in the original epic is Gawain’s hubris — he has a lot to learn about himself and how chivalry works. Though we are meant to feel sympathy for Gawain, it seems like these symmetrically composed shots are meant to allow us an inescapable feeling of isolation — a great way to visually represent Gawain’s self-centeredness without dragging us through a bunch of narrative exposition. Gawain is out of touch and in search of his place in the kingdom, so these shots evoke that it’s “Gawain Against the World.”

Lighting the Interiors

Sometimes one of the hardest parts of lighting a scene is making the decision to light realistically — as in lighting your subjects from the direction the light would actually be coming from, or to make specific creative decisions that serve the story rather than the practicality of the world you’re creating. With The Green Knight, Droz Palermo had to face the ultimate challenge. How do you light a dark hallway where there’s technically not supposed to be anything but candlelight to illuminate your actors?

Speaking with Cinematography World, Droz Palermo described the approach he took with lighting the interior hall scene that opens the film:

During that period of history, the bowels of any interior would have been incredibly dim, with the sun, fire, or candle light being the only sources of illumination. So I tried to hold on to that with single-source, single-direction lighting as much as possible. However I did need to add some fill, sometimes with a balloon or SkyPanels here and there, in the bigger spaces, and had 18K HMI or Wendy lights pushing in daylight from outside. I like mixed colour temperatures in the image, so I let the daylight go cool, the fire/candle light be warm, and soft-lit faces between 4,000 and 5,000 Kelvin.

Good cinematography is very similar to good editing. If it’s really working, you might not notice it at all. Some of those opening scenes at the round table are among the most memorable, but none of the shots look so stylized that they’d take you out of the scene.

The Final Sequence

Of all the shots and sequences in The Green Knight, the 20-minute sequence toward the end of the film might just be a perfect case study for the entire approach that Droz Palermo and Lowery took with shooting this movie. It’s no secret that movies have the power to tell you a story in many different ways. One of those methods is subconsciously visual — as in, you don’t know why you feel a certain way, but you do. That feeling can stick with you long after you leave the theater, and it keeps you coming back to the film for years after its release.

While shot with a 58mm lens, the shots featured in that final sequence are everything Droz Palermo and Lowery had been showing us throughout the film — only amplified. We can’t help but feel this is taking place in the same world we’ve been living in for the past two hours. It’s a way to instantly trigger this specific emotion in the audience without relying on unnecessary exposition.

The lenses used in this sequence require a center-focused, center-framed, wide-open shot due to the intense focus fall-off the further you move from the center of the frame. Take, for example, the shot above with Gawain in focus but nobody else — even though they are all on the same plane. These symmetrical compositions really benefited from this specific type of glass. Those T-type lenses provided that weathered characteristic that Droz Palermo needed. Note the intensity of the swirl and distortion of the image toward the edge of the frame.

Interested in more cinematography insight? Check out this look behind the scenes of The French Dispatch with long-time Wes Anderson DP Robert Yeoman.

Feature image via A24 and Eric Zachanowich.