“You have to ask yourself,” says Mohammad Gorjestani, filmmaker and co-founder of Even/Odd, “Have you spent time in the community or similar communities outside of the project? Do your identity or experiences lend a unique perspective to the project? If the gap between the story and the storyteller is too wide, then it needs to be challenged. This isn’t about identity politics, I’m not suggesting a world where you make work solely based on your identity—but more of a thoughtful approach to how we consider the storyteller as much as the story in the service of making more singular work, rather than platitude and derivative-like projects that only reinforce the current power structure and dynamic.

These questions become even more important when brand funding is involved, which can call intention and authenticity into doubt.

“There’s this word that’s been thrown around so much now,” Gorjestani says. “Authenticity. It’s jumped the shark and is a meaningless word that’s been used in preach but not in practice. Authenticity means that in the deep fabric of the work, there is a level of truth in the minutia, spirit, and details that the custodians of a culture or a place pick up on it.”

The Iranian-born filmmaker directed several films for Square’s For Every Dream series, including Exit 12: Moved By War, Made In Iowa, Sister Hearts, and Yassin Falafel. Each work represents a reimagined take on the American Dream.

How did you get into filmmaking?

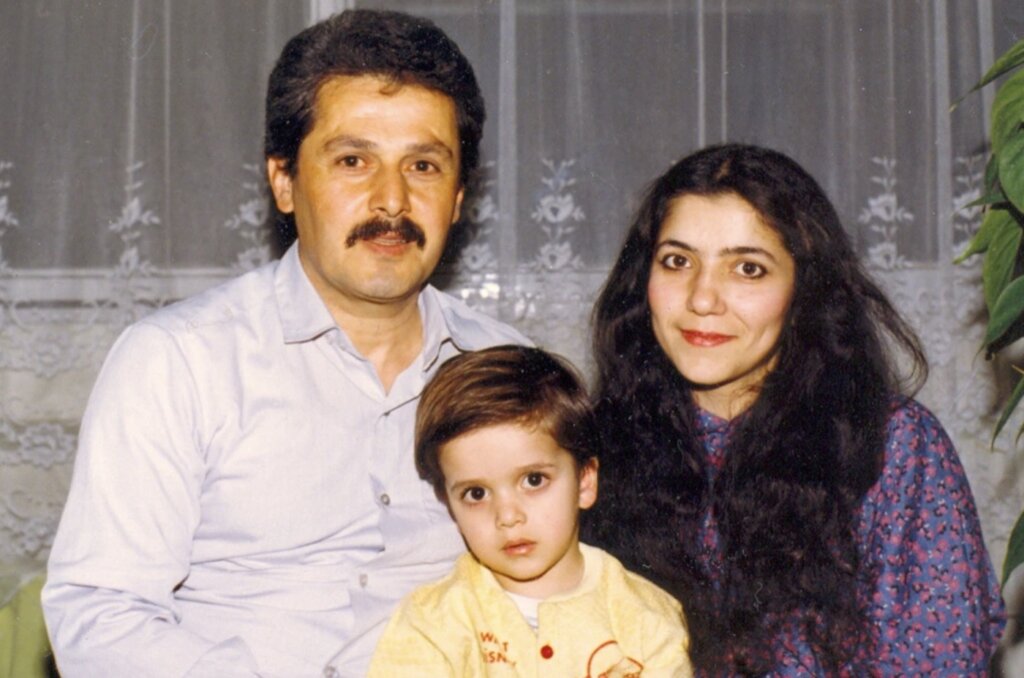

I think my DNA was rooted in creativity. My mom is a painter, and my dad is a sculptor, painter, and graphic designer. They were artists in Iran—my dad was an art professor at Tehran University and my mom was an emerging painter. Then the revolution happened, and the Iran/Iraq war happened. And like a lot of Iranians during this time, we left believing there was a better opportunity in the United States.

I was really into photography and started placing stories with images. When I was 19, I had a friend that had just gotten a GL2 camera. I borrowed it for three months, and I just messed around with the thing and shot stuff. I was playing music a little bit at the time, so I started putting that music against what I shot. None of it was good, but it was something that hooked me enough to want to keep going back to it.

How did your experiences shape Even/Odd?

While we were building the company, I was still trying to create language for the feelings I had, build my belief systems, define them, and articulate them in a concise, clear way.

Every time we make something, every time I’ve made something, I’ve moved the needle forward in identifying what it is that I do and who I am or what I want to put in the world.

I have this point of view, and people see the value of that. But then they want to adjust it to make it more palatable or marketable. It’s a lack of creative equity. We talk about equity a lot economically, but we don’t talk about it enough culturally and creatively. The way it shows up is when people try to take your experience and put it through their often Western and white-influenced filter of what is “good” aesthetic and storytelling. So this idea—that I had to adjust who I am to get things made—started to wear on me, and it made me resentful especially when now looking back, I clearly see where I was pushed to not be myself to conform to things I don’t identify with. One thing I’ve learned and embraced is that I’m not good at not being myself.

How does Even/Odd’s mission translate to its projects?

We’ve created this company where multi-cultural, minority, or underrepresented experiences aren’t just something we celebrate for some flavor-of-the-month marketing campaign. For us, this is day-to-day; a natural progression of the life experiences that have informed those who are at the creative helm of our projects and stories. Every day I wake up as an Iranian who grew up in low-income America—specifically in the Bay Area. I don’t turn that off and on based on the month. It is a complex experience that informs my creative work and can’t be generalized.

Even/Odd protects that perspective as much as anything else.

Even/Odd exists to support filmmakers and artists who want to base their storytelling universe around the places they have been entrenched in and the things in the world that have influenced their lives—and out of that, they’ve also created their own aesthetic to reflect it.

“When you actually practice an inclusive process top down and bottom up, you’re just going to make better work. It’s the nuances and the details of every project that make it special.”

Mohammad Gorjestani

The creatives we support have a stake in the world their projects are told in. I like to say that you should make work about the things that keep you up at night, and the things that get you up on your hardest days where you just want to hide under a rock. When you come from communities that are constantly under attack—by capitalism or racism or the powers and policies created from the past and present—it’s not an off-and-on switch between your life and your work. It’s all part of one, albeit sometimes very fractured, but ultimately intersecting existence.

The industry has fallen short of going beyond the “check box” when it comes to diversity and using it just to save face as part of some crisis PR campaign. You can see that now in 2023 when so many things are going backward—I just watched a Ramadan commercial that had no Muslims working on the project. That’s odd to me, and it’s more odd that no one has noticed that. To me, making work inclusively from the inside out is the ultimate cheat code—because that’s how you make the best and most effective work.

What makes a work authentic?

Work is authentic when the people who are being represented feel that their actual cultural identity inside of their community is accurate, based on their own community’s perspective.

On the documentary side, it’s important to build a more authentic relationship with the subject. You have to relate to your subject matter in some kind of way where you have a stake in it, too.

I don’t believe in monoliths. For example, I don’t believe only an Iranian can tell an Iranian story. But you have to be able to connect to the subject matter on a meaningful level. Including diverse perspectives is the best way to do this.

What makes a documentary authentic?

A documentary is authentic when your subject sees themselves in it or even sees a version of themselves they didn’t know existed, because of the aesthetics we’re putting on it. At the end of the day, when you see it, you feel it.

My interest and conviction in wanting to represent people help them reveal things. The most consistent feedback I’ve gotten from people is how they’ve never shared some of the things they’ve shared with me and our crew with anyone else, including their own family.

My interest and conviction in wanting to represent people help them open up. The most consistent feedback I’ve gotten from people is that they’ve never before shared some of the things they’ve shared with me and our crew—not even with their families.

People want these safe and effective spaces to share their experiences. They want to feel that their voice, opinion, perspective, and the things that they’ve gone through are important enough to be seen and heard.

Even/Odd does a great job of capturing authentic stories without exploitation. How do you advise other branded content studios to do the same?

It’s harder to exploit something if you also have a stake in the subject matter. There shouldn’t be that big of a gap between the community represented in your work and the community you spend your time in outside of work. I’m not saying it should be 1 to 1, but the gap is way too wide most of the time. If there is a big gap, there’s a problem, and that’s a hard thing for people to confront.

“People need to spend less time thinking through the lens of work and more through the lens of living.”

Mohammad Gorjestani

I think about the marriage of storytelling, aesthetics, and social issues. All three have to be held to a very high standard. On every project, one of those three is constantly getting compromised. That’s just the nature of living in a high-resource industry that exists inside of capitalism. It’s a very challenging thing to navigate, and I’m still figuring it out, to be honest.

How do you know if a story is worth pursuing?

I view it as a creative challenge. I’m constantly thinking about how to create new reference points, and I’m always interested in finding new ways of doing things.

In a story-driven project, is the protagonist an active member of their own narrative? Or are they just an absorber of things other people are doing?

If you look at Exit 12: Moved By War or Sister Hearts, neither protagonist had anybody else. No one handed them anything. A product didn’t save their lives.

When you can actually look at the work and say—‘Well, the antagonist here was the societal system that made this unreasonably hard for them in the first place’—those are the kinds of things I’m looking for.

As a filmmaker, how has your relationship with music changed?

I’ve actually embraced music more over the last few years. For Exit 12: Moved By War, I wanted that film to feel like a night at the ballet or a night at the theater. It’s the power of those instruments, all of them played by composer William Ryan Fritch, that really delivered that feeling and accentuated the classical nature of the imagery.

Ultimately, music is like a paintbrush that’s available to the filmmaker. I’m interested in hearing something that can work for a film and can change the way I think about images. That’s a very exciting thing to realize as a filmmaker.