Filmmaking isn’t immune to trends. Filmmakers are community-based, which means we see what our peers are making, and it inspires us to do something similar. You see it in Hollywood all the time. We went through our vampire era, our zombies phase, and now we’re fully embedded in the superhero trend. Does anyone remember the oversaturated colors of the early 2000s? Or the handheld camerawork that came after? The cycle is inescapable, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

But, there is another opportunity on the table, one that many filmmakers tend to overlook. We’re busy poring over the latest techniques, cameras, and storytelling styles, sometimes forgetting about the giants upon whose shoulders we stand—classic cinema. If you’re looking to get out of a creative rut or find something genuinely new and interesting in our industry, there may be no better place to find it than in a classic film — for a few reasons.

First, these films were part of their own trends. You can pull different elements and assemble them in your own way (it’s called the art of stealing, something we’ve tackled before). Just look at the experimental editing of the ‘70s or the ornate set design of the ‘60s. Every era has its own stamp, and many of them are worth drawing from.

Second, classic films are classic because, well, they’re great films, which means they’re worth a second or third or 28th look. As Roger Ebert once said, “Every great film should seem new every time you see it.” And, we don’t just mean they’re great for their time. They’re great movies now. With that in mind, we decided to take a look at seven classic films and extract some key lessons.

Here are seven lessons from classic movies.

1. 12 Angry Men—Humanize Your Drama

On paper, 12 Angry Men sounds a little boring. Here’s a full-length movie about 12 men sitting in a room and deciding the fate of a teenage boy accused of murder. It sounds uninteresting until you start watching and notice that it draws you in much like a thriller would—full of tension, uneasiness, and more than a few powerful moments. Why is that? The characters.

This film is a powerful reminder that conflict between people is the most compelling form of conflict. While the film doesn’t name the characters until the end, they’re each motivated by something deeper: bigotry, fear, ignorance, respect for human life — you name it. You may not agree with each of the characters’ motivations, but you can surely understand them, which makes for a compelling film.

If you take one thing away from this movie, recognize that good characters are the core of a good movie. Give them real motivations for their viewpoints and then bring them together in a dramatic collision. Try to understand why your protagonist or antagonist feels the way they do, and you’ll be well on your way to an interesting script, no matter the setting.

2. Jurassic Park—Never Underestimate Restraint

Before we dive into Jurassic Park, take a minute to watch the original trailer for the movie.

…compared to the trailer for the newest movie…

Notice the difference? The first film has almost no shots of creatures or VFX; it spends more than two minutes building a mood and teasing what’s just off-screen. The latter, of course, is full of creature effects. That method of suspense building from the original trailer carries into the movie as well, withholding its big reveals until the tension reaches a boiling point.

To us, it’s interesting because Steven Spielberg made a choice. As we all know by now, Jurassic Park’s effects were good enough to show in the trailer. Unlike films like Jaws or Alien, where Spielberg perfected the technique of using secrecy to distract the audience from the lack of technology for effects, Jurassic Park could have laid all of its cards on the table, but Spielberg chose otherwise.

You’re probably wondering what this has to do with a filmmaker who isn’t even making the next installment of the Jurassic Park franchise. The takeaway here is that you don’t need high-end effects to build tension. In fact, high-end effects are often detrimental to tension. Whether you’re making a thriller, an indie drama, or a 30-second TV spot, recognize that there’s value in hinting at something that’s much deeper or darker in our imagination than any effect could be. The only thing more valuable than a spectacle is the anticipation of one. Don’t sacrifice it freely.

3. Seven Samurai—Never Underestimate Simplicity

It’s easy to think that something needs to be new to be great when, in fact, it just needs to be meaningful. No one understood this better than Akira Kurosawa. Pick just about any of his movies, and you’ll see a nearly elemental approach to filmmaking: breaking down characters to their simplest, most understandable form. He even instructed his actors to pick one gesture over and over for their character, to drive home one simple emotion.

In probably his most renowned piece of work, Seven Samurai, Kurosawa puts this philosophy on display. It’s a beautifully simple film with beautifully simple techniques. His characters are archetypal—there’s the “serious one,” the “funny one,” the “inexperienced one,” the “wise one,” and so on. The plot is straightforward, too. A ragtag group of samurai need to defend a village from invaders. Even the camera techniques are simple, focusing on expressions, the weather, and how emotions tie the two together.

This isn’t to say that Kurosawa didn’t use innovative techniques in his films, but Seven Samurai tells a simple story intentionally. It acknowledges that life and interactions between people don’t have to be complicated to be compelling. In fact, the more understandable and relatable an interaction is, the more people will connect with it. In a medium where “high art” tends to fall into a difficult-to-understand category, try innovating by creating a story so great that everyone will understand it.

4. The Third Man—Don’t Be Afraid of Style

If you can say one thing about film noir, it’s that it was an era of film that was dripping with style. You have the dynamic lighting, the tight angles, the moody atmosphere, the twisting plots—which all add up to an unforgettable, cinematic shorthand. Good or bad, it’s very memorable. In the case of The Third Man, possibly the best film of the era, not a single frame goes to waste.

In filmmaking, a recognizable style can be a strategic storytelling choice. Take, for instance, the films of Wes Anderson. His style is incredibly specific, and he uses that as part of his narrative. A Wes Anderson film is a particular type of experience, and audiences know to watch it in a specific manner. It’s a technique that’s been very successful for Anderson.

For director Carol Reed, style is integral to the storytelling in The Third Man. The angular, Art Deco-staging of the streets of Vienna, the 4:3 aspect ratio, and his famous use of the Dutch angle all contribute to the confusion, the atmosphere, and the narrative. The point is this: don’t be afraid of style. Filmmaking is a visual art form, so only going with a “natural” filmmaking style can create missed opportunities. Play with the angles. Play with the aspect ratio. Play with the design. Make the film only you can make.

5. Fargo—Don’t Coddle Your Characters

Some writers protect their characters. They write from a standpoint of empathy, and they consciously or subconsciously want the people in their story to make the right decisions. It feels good while you’re writing, but it makes for a boring movie. We need our characters to make terrible decisions and the audience to think, “Oh no, don’t do that.”

No one does this better than the Coen Brothers. Their films are full of characters making terrible decisions and putting themselves between a rock and a very hard place. Perhaps no film demonstrates this quite like Fargo. The entire plot is built on the main character, whose initial bad decision leads to many, many more poor decisions. You know he shouldn’t have his own wife kidnapped by bumbling criminals, but you can’t wait to see what happens when he does. It’s both cringeworthy and captivating.

As you’re writing, avoid the tendency to write from a place of comfort. Don’t protect your characters. It’ll make for a more interesting story and force you to make creative decisions. Know your characters’ motivations, have them make decisions based on their motivations, and then make them pay dearly for it.

6. Dr. Strangelove—Respect Your Audience

We’ve already covered one comedy on this list, but now let’s talk about its cousin: satire. It’s a tricky thing to do from a writing standpoint, to walk the line between a compelling examination of life and something that’s simply preachy. We’d highly recommend watching Don’t Look Up and then watching Dr. Strangelove.

While Don’t Look Up is a decidedly clever film, Dr. Strangelove is a classic—smart, insightful, and (most importantly) funny. The difference is that Stanley Kubrick approached the film like an inside joke, and he let the audience in on it. He wasn’t taking a high-and-mighty stance; he was simply turning the light on and letting us see what he saw.

As a writer, it’s important to think of your audience as intelligent and empathetic. If you think you’re writing to morons, then your writing is going to sound moronic. But, if you write for intelligent people who care deeply about causes as much as you do, then writing is going to come across as nuanced and subtle—much like life itself.

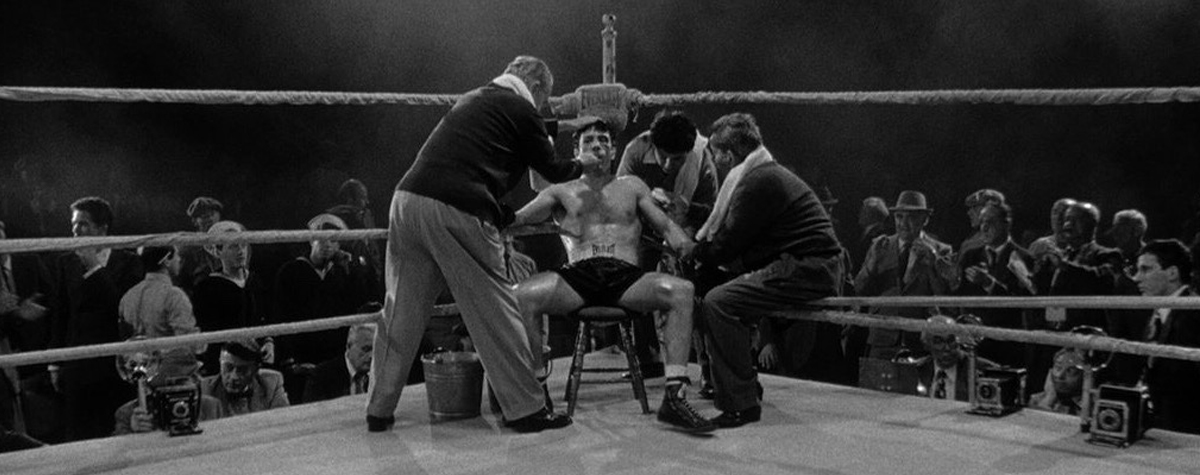

7. Raging Bull—Edit for the Emotion

If you want to watch a masterclass in film editing, just watch Raging Bull. There’s a good reason why it’s considered one of the best-edited films of all time. Whether you’re watching Jake LaMotta’s personal life fall apart or you’re watching him obliterate his opponents in the ring, you know there’s something special about what’s happening. There’s something more to the cut. Here’s a quote from the film’s editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, about her relationship with director Martin Scorsese:

“All great directors or anyone who has a strong vision like Scorsese needs to have a lot of support around them. I think from the very beginning—when we met each other—he realized he could trust me to do what was right for his movies.”

Studios were famously nervous about Raging Bull. Even Scorsese himself said he thought it may be the end of his career. A big reason for the apprehension was because his vision for the film required a cut that didn’t adhere to traditional narratives. It needed something different. It needed Schoonmaker.

The editing of Raging Bull is all about emotion. In many ways, the film forgoes realism and continuity for the sake of cementing what’s actually happening to the characters. Every fight that the main character goes through represents something that’s happening in his mind. It’s cerebral, and so is the edit. Ultimately, the lesson here is to edit for the film. Sacrifice everything for the feeling you want the audience to take away from the scene. If it doesn’t come across as realistic or believable, make your audience believe what they’re feeling is real. It’s all that matters.